Fritton (nr. Great Yarmouth) (†Norwich) C.12

Martyrdom of St Edmund & other subjects

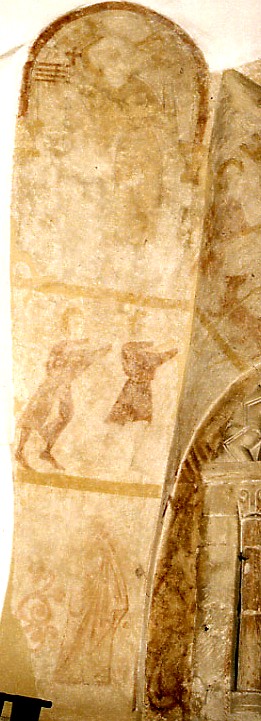

Above is the apse in the ancient church at Fritton, painted with the Martyrdom of King Edmund of the East Angles. The Martyrdom itself is in the triangular area above the rounded arch (the stained glass is modern) and flanking it are two very faint figures representing the True Church (left) and Unbelief or Paganism (right). Below these two figures are four archers, two on either side, shooting at Edmund. Below these again are, on the right, a saint who may be Peter, and on the left an unknown figure without a halo who may be the donor.

At the left is the central portion, showing in the centre the fragmentary figure of Edmund himself standing beside and possibly tied to, the slender tree on the right. There is virtually nothing left of his figure apart from his crown, which has a square, castellated top like a battlemented parapet. But various arrows, piercing the tree as well as Edmund, show fairly clearly , and a figure who is probably the huntsman who found the king’s body stands at the far left, possibly pulling out one of the arrows.

Lower down is an allusion to one of the most popular legends about Edmund, that of the wolf (or dog) who found his severed head. The creature stands on its hind legs, front paws braced, presumably against another tree, head turned to look at the saint. The story of the wolf who guarded Edmund’s head until it was found was enormously popular, especially in East Anglia, and there is a bench-end carved with the wolf and the head at Hoxne in Suffolk, which has always claimed to be the true place of the martyrdom.

The photograph at the right shows the left hand side of the apse wall. There are three tiers, and there is is very little left of the subject at the top, but the symbolic figure representing the True Church (top left) holds a small red-painted cross (possibly once a processional Cross with a long shaft). There may be a building in the background, and/or the figure may hold a model of a church. Immediately below are the two archers, and below them the unidentified figure who is either a donor or a saint. The photograph below left shows the right-hand side.

The most important thing about the figure at the top right, representing Unbelief or Paganism is that she is spilling water from a pitcher (detail, top right). As a general rule, this figure, who is also sometimes described as ‘Synagogue’ and represents the limitations of the Old Law, is blindfolded and has a broken staff. It is impossible now to know whether the broken staff and blindfold were once visible here. There is no association with an upturned pitcher as far as I know, but spilling water is sometimes an attribute of Intemperance, Excess or Emptiness in its metaphorical meaning of ‘Vanitas’. There may simply be confusion about categories of personification here; alternatively, it is possible that the emphasis is on Blind Ignorance, which understands nothing and whose teaching is thus vain. In some ways the figure is close to a minor allegorical character in Spenser’s sprawling 16th century epic The Faerie Queene, who spills the water from her pitcher and runs away in fear when she encounters personified Truth¹.

Two more archers are below this figure, one of them with legs very elegantly crossed, and below them is a haloed figure with what is possibly a key at the top left. St Peter is thus a possibility, but if this is a key, the figure is not holding it, and other names, such as St Felix (of Dunwich) the 7th century Burgundian evangelist and later bishop of the East Angles, or his Irish contemporary St Fursey, who founded a monastery at nearby Burgh Castle, have been suggested.

Incomplete and faint as these paintings now are, they are important as early survivals in the commemoration history of a very popular saint. The ancient carving around the arch of the apse is visible in the photographs; the two iron rings which once supported the Lenten Veil in front of the Sanctuary are still there, and the fourteenth century painting of St Christopher in the nave is also on these pages.

¹ Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queene:Books 1-111; ed. D. Brooks-Davies, Everyman, 1987, Book 1, Cantos X-X1. Spenser’s character runs home to her equally ignorant mother, called Corceca (‘blind of heart’, as in Ephesians 4:18). Spenser’s context is a Reformation one of Catholic v. Protestant, but the structural similarity in the allegory remains, I think.