Coombes, West Sussex (‡ Chichester) 1150-1200

Christ in Majesty (Maestà), with Traditio Legis and an Illusionistic Painted Figure

The central area of the painting, with Christ sitting in an almond-shaped mandorla flanked by two Seraphs, is faded almost into invisibility now. His pierced feet, overlapping the lower edge of the mandorla, are perhaps the clearest detail, but what remains here is enough to show the quality, comparable to the paintings of the same subject at Clayton also in West Sussex. Also remaining, and clearer at the left, beyond the Seraph, is the sole remaining Evangelist symbol, the lion of St Mark. The lion faces left, but turns its head back to look towards the central scene.

Below the lion, whose foot overlaps the edge, is a painting of the Traditio Legis – the giving of the Keys to St Peter and the Book to St Paul. Christ sits centrally; his head is now completely obscured, but his right hand and the key he holds out towards a now disappeared St Peter are clearer. The figure of Paul at the right is almost intact – heavily bearded in the traditional manner, he bends in reverence as Christ hands him the book.

As with other very early wallpaintings in England, the true fresco Coombes examples, with their elongated, large-eyed figures, have a markedly ‘Greek’ or Byzantine air seen to best effect in the very full painted scheme at Kempley in Gloucestershire. It is a style of painting that disappears (or seems to disappear – as so often, we cannot know what has been lost) from England in later centuries. But the impression of remote iconic solemnity it conveys may in itself be misleading, and there is a visual joke at Coombes which I think may undercut all this grave seriousness (photo, right).

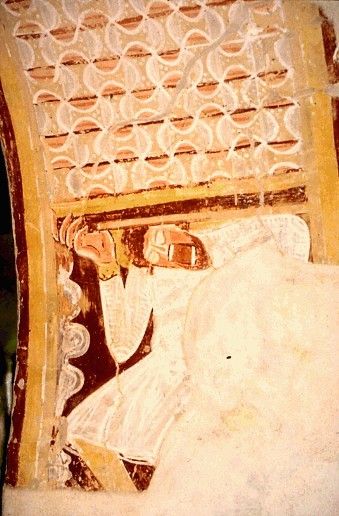

It is painted on the soffit of the chancel arch, and shows a figure literally supporting it. It is a most unexpected thing to find, and the danger with something like this is over-interpretation. The straining figure, face reflecting the crushing weight of the burden he bears may be called an atlas-figure (Caiger-Smith) or a caryatid (Rouse), but I am not sure if these descriptions really warrant extending the ‘interpretation’ of the painting into areas such as the Psychomachia of Prudentius and indeed the whole area of Greek philosophy and (or versus) early Christian belief in the first centuries of the common era. This is, after all, a tiny country church, and to judge by what is known about its early history, it was beset by difficulties from the first¹. And this, it occurs to me, may be part of the point – whatever else the toiling figure is, it is recognisably human, and certainly not dignified, distant or hieratic. Perhaps it is better to be grateful that the church survived long enough for the painted scheme to be made at all. I am not sure that we need Prudentius – the medieval love of jokes and visual puns may be all the explanation we need.

Also at Coombes, and also new at this update is a 12th century Flight into Egypt, together with King Herod and some of his attendants – these paintings almost the sole surviving scenes from what seems to have been a full Infancy Cycle. I will try to include the fragment of an Annunciation which also remains at a future update. There are also some 14th century paintings, but these in turn are very faded now. There is no doubt, though, that the early paintings at Coombes are worthy to stand beside those at Clayton, Hardham and West Chiltington, all part of what EW Tristram called the ‘Lewes Group’ of wallpaintings in Sussex.

¹ There is a useful account of some of these tribulations in this online extract from Sussex County Magazine. And there is more on Prudentius’ Psychomachia on this site on the page for the Allegorical Joust at Claverley.