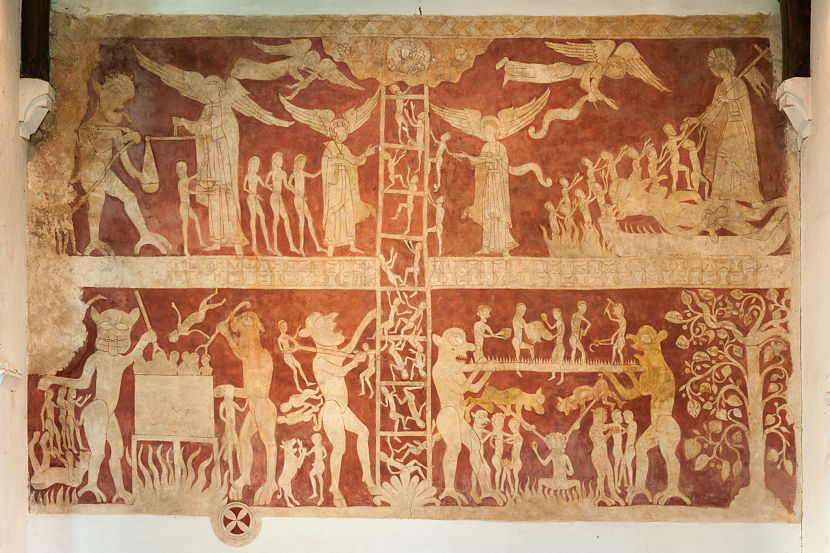

Chaldon, Surrey c.1200

The Purgatorial Ladder, or Ladder of Souls, with the Seven Deadly Sins

Comparisons of this remarkable painting are impossible. It is unique in the fullest sense of that much-abused word, and there is simply nothing else, in England, or as far as I know, elsewhere, to compare it with. My own feeling is that it owes as much to medieval literary sources – sources probably now long since lost – as to iconography. Medieval dream narratives such as The Dream of the Rood and even Piers Plowman (although the Chaldon Ladder is much earlier than this latter) come to mind. So indeed does the Divina Commedia of Dante and comparable contemporary works involving the soul’s spiritual journey. The Chaldon Ladder is said to be the remaining fragment of a larger scheme including, on the north wall, scenes from the Fall of Man, but nothing remains of this or any other painting in the church. Perhaps the closest thematic resemblance to any other painting on this site is to the Allegory of the Penitent and Impenitent Soul at Swanbourne, although that is much later and stylistically very different.

The painting is best ‘read’ starting in the lower left-hand quadrant, and unequivocally, in Hell, where the Seven Deadly Sins are receiving punishment. Part of the left-hand edge of the painting is missing, but beyond this to the right, below the extended arm of a gigantic devil facing outward towards the onlooker, three tiny people, naked to represent souls, proceed to the right with what Tristram described as ‘a leisurely gait’ while below them as they stroll a devilish four-footed beast lies on its back to gnaw at their feet. This is Sloth, first of the Sins. Moving right, another group of unfortunates is tortured in a square cauldron placed over a fire, while another falls headlong into it. Another large reddish devil assists with the punishment, wielding a suitably pronged instrument.

Between this devil and the cauldron, another, slightly taller naked soul represents Gluttony, as indicated by its clutching a bottle of wine (enlarged detail, right). Gluttony in the Middle Ages is represented with depressing frequency as a liking for strong drink, rather than food, and there is a comparable instance at Trotton in the painting of the Seven Deadly Sins there. Tristram described this soul as a pilgrim who has cast aside his bourdon or pilgrim’s staff and garment, and the enlarged detail at the left makes this clear enough.

Moving right again,the next sin represented is Pride, shown as a woman and a small devil standing between two of the large ones. The devil grasps the woman by the wrist, drawing attention to a ring she wears and is evidently proud of (this is Tristram’s reading, and I certainly see no reason to dispute it). Directly above this pair, and shown as falling from the back of a tall devil to the right, two people, one a woman, I think, dispute possession of what seems to be a horn or cornucopia, an object which may or may not have special meaning. In any event Tristram interpreted their struggle to possess this as symbolic of the next Deadly Sin, that of Anger, and once again, this seems reasonable to me.

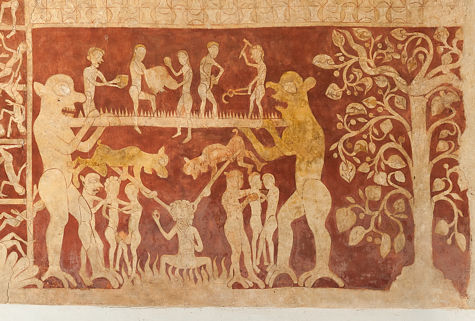

Next right, another large devil with hooves grasps the Ladder which divides the painting vertically, while on the ladder itself, souls try, and in this lower half of the painting fail, to climb upwards on it, with some shown as desperately clinging to its edge while others fall headlong. On the other side of the ladder, in the lower right-hand quadrant of the painting, the three remaining sins are dealt with. First comes Lust, shown as a man and woman embracing, while a smaller devil with a grimly disapproving expression grasps the man by the shoulder, thus curtailing any kind of consummation. After Lust comes Avarice, one of the clearer and more readily readable details. A man, with a bag of money hanging around his neck and wearing a belt from which hang three more, sits astride a fire, right hand raised in helpless protest, forced to count the coins that pour from his mouth as two devils hold him in position with pronged forks. Finally, to the right of Avarice comes Envy, where Tristram describes the symbolism thus ‘a devil puts his hand on the aged figure of a soul, who is grasping a younger companion, as though envious of his youth’².

This completes the symbolic representation of specific punishment for itemised sinful transgressions, but it is not the end of matter. The painterly hand that made this scheme has brought in other details to emphasise both the condign nature of punishment for sin, and the eternal nature of Hell. On either side of the miser with his moneybags, two large devils hold each end of a razor-spiked beam, upon which souls attempt to perform tasks foredoomed to hopelessness, since there is, after all, no hope in Hell. At the left-hand end of the beam, a potter attempts to shape a pot without a wheel, while at the far right a blacksmith tries to make a horseshoe without an anvil. Tristram also identified a woman trying to spin without a distaff, and there are evidently other attempts at activity going on, but there has been damage to the painting in this area, making it hard to be sure about some of the detail. The overall message is plain enough however: for the unredeemable, labour continues in Hell, but the fruits of that labour can never now be realised.

The final significant detail in this quadrant of the painting is the source of all evil. The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil is shown at the extreme right, with the serpent coiled in its upper branches. As descendants of Adam and Eve, Original Sin has brought the souls in Hell to this, and their failure to obtain reedeming Grace in life, or to be purged of their sins in Purgatory, has sealed their fate for ever.

The upper right hand quadrant of the painting shows the fate of more fortunate souls, who, in this painter’s theology at least, have avoided eternal damnation and are scaling the purgatorial ladder, which ultimately leads to the eternal realm of Heaven. Here, in a scene more familiar in English wallpainting from depictions of the Harrowing of Hell, Satan lies, bound, not on a bed of flames, but on a giant worm, or wormlike creature, extended to its full length, with huge eyes and the beak of a cockerel³. This creature bites Satan’s head, while Christ stands over him, driving the banner-staff of the vexillum into his mouth. Redeemed souls, hands extended in supplication, proceed out of the flames towards his extended right hand. At the left, a standing angel encourages a soul upwards on the ladder, while another soul waits near it, grasping the upright of the ladder with confidence. This standing angel has a speech-scroll, as does an angel flying overhead towards the figure of Christ Both are unreadable now, but no doubt once bore welcoming words such as those carried by angels in the Doom at South Leigh. As to the two souls about to climb the ladder, I think it is perfectly possible, even likely, that, as asserted in the church leaflet, these are intended for Enoch (Genesis 5:22 & Hebrews 11:5) and Elijah (11 Kings 2:11), in Bible typology two of the righteous of Old Testament times who were ‘translated’ before the apocalyptic judgement and so did not taste death in the normal human manner.*

Finally, in the upper left quadrant, and again familiar from other medieval wallpaintings, is the Weighing of Souls. Here a devil hauls a group of souls, only hints of legs remaining visible because of damage to the edge of the painting, towards St Michael, standing ready with the balance, where, as so often, another devil tries to weight down the scale pan as a soul is about to climb onto it. On the other side of Michael, three Saved souls walk towards the upper part of the ladder while another angel ushers them on to it with an encouraging gesture. These may be simply representative souls who have been weighed in the balance and not found wanting, or they may, as asserted in the church leaflet, be intended as the Three Maries who went to the tomb of Jesus after the Crucifixion and found it empty. All are clearly female, and it may well be that these earliest women witnesses to the Resurrection have been thus singled out for their special holiness. An attractive idea, at any rate. Above, a flying angel carries another soul, by implication an even more holy one, directly to Heaven, but speculation about who this might be is idle, I think.

The eschatology, and indeed the entire theological scheme informing this painting is immensely complex, and it would remain so even if we knew anything at all about the identity of the painter. There are comparisons to be made with other paintings on this site, of course – the allegory at Swanbourne mentioned above, along with all paintings of the Seven Deadly Sins. Then there are the painted eschatologies of comparably early date at Kempley, Clayton and Hardham. The medieval Doom painting is relevant as well, but in the end, the Chaldon Ladder is, and probably always was, a unique and extraordinary product of the human imagination.

You can see a 360° panorama of the interior of the church here.

Website for SS Peter & Paul, Chaldon

¹ Tristram 1, p.108

² ibid, p. 109

³ On Satan and the ‘worm’ Isaiah 14:11 with its prophetic song of triumph at the eventual vanquishing of Satan, may be of some relevance, as may Isaiah 66:24, and the ‘worm that dieth not’. In more homely terms, the worm’s ‘mixed’ animal nature, like that of the devil in the Weighing of Souls at Bartlow (where there is further discussion of the medieval attitude to mixed natures) is appropriate to a denizen of Hell.

*Special note on Bible typology. For complex matters such as the ‘translation’ of Enoch and Elijah, a good, scholarly Bible commentary such as the single-volume New Bible Commentary published by the Inter-Varsity Press, Leicester, England, is the best recourse for consultation.

Photos © Roy Reed 2019