Hessett, Suffolk (†St Edmundsbury & Ipswich) C.15

The Seven Deadly Sins

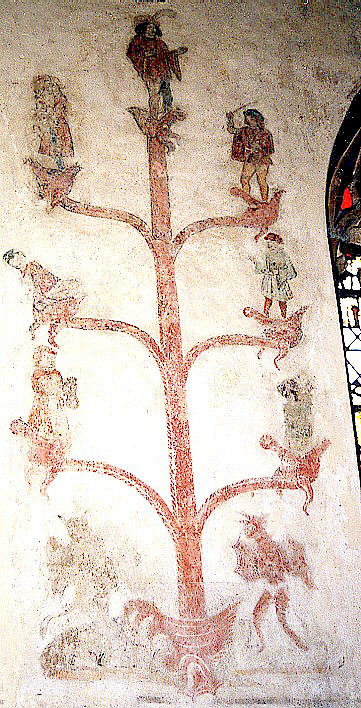

Painted above the Warning to Sabbath Breakers at Hessett is the Tree of the Seven Deadly Sins shown on the left. It is in generally very good condition and only in a very few English paintings of this subject are the individual sins as well preserved. All seven are reasonably clear, and all are personified as small figures issuing out of monstrous mouths, very like those at South Leigh. The Tree itself grows out of a larger mouth at the bottom of the painting, and two attendant devils stand beside it.

Generally, medieval written sources dealing with the Seven Deadly Sins – most of them intended for the instruction of the laity – observe a regular hierarchy of sins in descending order of reprehensibility, but English wall paintings often depart from this scheme. Always, though, Pride, the sin for which Lucifer fell, leads all the rest.

Here Pride is at the apex – the central figure at the top of the trunk of the tree (detail right). Unlike the example at Raunds and but in accord with those at Hoxne and Little Horwood, the figure representing Pride is male – a very stylishly dressed young gallant with bi-coloured hose, short tunic, huge sleeves and a plumed hat. He holds out his hands, as though for our admiration.

At a slightly lower level, branches holding two more figures spring from the trunk. These are, at the left and pictured below (left), Lust¹, represented by two figures embracing. The detail is faded, but the male participant is on the left (with blue hose in evidence again), and the female on the right, with a red robe and, I think, a kerchief on her head. The heads of the two, meeting in what is obviously a passionate kiss, can with persistence be made out.

On the other side of the trunk, and shown below right, is Wrath, again a fashionable young man in yellow hose. In his left hand he holds a dagger, the hilt of which is still just discernible, and he may be wounding himself with it. In his raised right hand he has a whip, for the purpose of lashing those against whom his wrath is directed and also, importantly, himself. Representations of self-flagellation (of the non-pious kind) were familiar symbols of the corrosive effects on the soul of anger, as indeed was the dagger, usually shown as rusty, aimed at the self.

On the next pair of branches below are Sloth and Envy, neither of them easy to paint as personified human figures.Sloth (below left) has been rendered as a figure leaning backwards and almost falling of his branch in lassitude.

He is probably asleep, and may be weighed down by some symbolic object in his lap. Envy, on the branch opposite and shown at the right below here, can at least be shown by appropriate colour – a green robe.

The painter has, I think, gone further than this though – Envy’s face is gaunt, almost cadaverous, and the emphasis is on the self-consuming nature of the sin. Once again, the corrosion of the immortal soul is insisted upon, and that is why these sins are Deadly.

Finally, on the lowest branches, come Avarice (below left) and Gluttony (below right). Avarice, reasonably clear, grasps a bag of money, obviously intending to keep a firm hold on it. This looks more like a female than a male figure, and this is possible. I suspect that we may have here a perennial medieval focus for indignation, the seller of short-weight bread, in a baker’s apron and mob-cap. At the Assize of Bread at Greenwich in April 1327, Alice Makejoye, Alice atte Schoppe, Alice Simekyns, Agnes le Pilcheres and Christine de Hoo were all arraigned for selling loaves below the prescribed weight².

Women predominate in the full list of offenders, who were clearly seen in much the same light as the fraudulent ale-wives who are sometimes seen getting their just desserts in Hell. Finally at the lowest right and shown at the right here, is the least clear detail, Gluttony, who does not seem to be the customary vomiting figure, but one gnawing avidly at some large, roughly circular, piece of food (the general impression of this is actually clearer in the main photograph above). Like Avarice.

But medieval churchmen and homilists, like Chaucer’s Parson with his endless subdivisions³, spun complex elaborations and built minute analyses on these basic categories of sin.

But all of them, unchecked, led to the place of damnation whence they came, and Hell (below left) is represented by another large Mouth, similar to those holding the individual sins. Two bat-winged and horned devils stand beside it, the one at the right faded but reasonably clear.

This painting certainly has a claim to be the fullest and clearest Seven Deadly Sins in the English church, and there are several other paintings at Hessett, including a Warning to Sabbath Breakers and a St Barbara, with her tower. There is also some very fine medieval stained glass. Some examples of medieval embroidery from Hessett – a very rare burse showing St Veronica’s veil and the Agnus Dei, and an equally rare sindon for veiling a hanging pyx at Mass – are now in the British Museum, and there are photographs of both in the church.

Website of St Ethelbert’s, Hessett

¹ Not Greed drinking something, as MR James, who had no modern technology to help him see it, thought (Suffolk & Norfolk, p.74)

² Public Record Office; Court Roll (Manor of Greenwich) Gen. Ser. 181/14 m.1.d. Fuller details in Edith Rickert, Chaucer’s World, p. 84 (OUP, 1948)

³ [e.g. stemming from Pride…] “…There is Inobedience, Avauntage, Ypocrisie, Despit, Arrogance…Veyne Glorie, and many another twig that I kan nat declare”, Canterbury Tales; The Parson’s Tale, 390

† in page heading = Diocese