Cranborne, Dorset (†Salisbury [Sarum]) c.1400

The Seven Deadly Sins

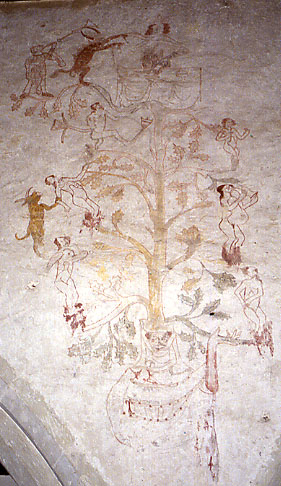

This painting of the Seven Deadly Sins has been ‘almost entirely repainted in outline’ according to Tristam, and there are certainly details here where repainting is over-obvious and over-heavy, but I am not convinced that the finished product has been falsified as severely as Tristram thought. Like many other paintings of this subject, though, it has its idiosyncrasies and puzzles, and very few of the individual sins can be identified with certainty.

At the top of the painting on the left, a man dressed in the kind of tabard usually associated with heralds blows a long trumpet in the direction of a reddish horned devil (detail, right), and this devil in turn reaches towards a table with an elaborately swagged cloth. At the table (below, left) sits a man, possibly wearing a crown, holding a knife and preparing to feast on an array of dishes set before him. This, I think, is not the sin of Gluttony, which is accounted for elsewhere, but Pride, from which all other sins were believed to flow – the lavishly set table and the presence, as at Alveley, of the trumpeter, point to this. It is, though, very hard to be sure, and most of the other sins are unidentifable.

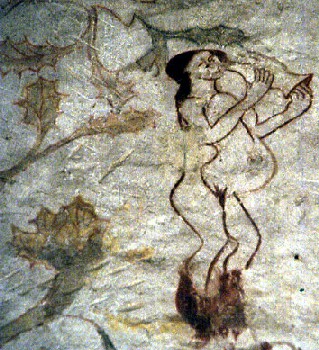

They are arranged as branches of a tree, perhaps intended for holly and certainly bearing prickly-looking leaves. The most obvious candidate for the sin of Gluttony is the figure drinking from an ewer on the right of the tree, and shown in detail below at the left. The grossly bulging abdomen of this figure is presumably intended to convey the extent of the greed.

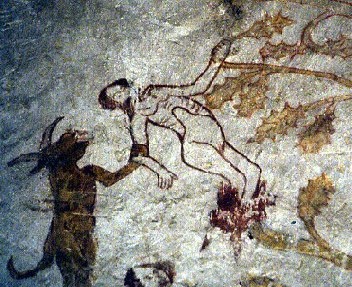

But there is nevertheless an element of guesswork here, especially in view of the restoration, which may have introduced elements not originally present. Much the same applies to a figure on the other side of the tree: this figure (detail, below) leans backwards at a perilous angle and his arm is grasped by another horned devil. Very possibly this is intended for Sloth, but it is impossible to be more specific about the remaining sins.

At all events, the root of the Tree, and thus of evil, is shown here, as it is in most tree-diagram examples of this subject. Some of the examples on these pages – Hoxne for instance, with its devils sawing through the trunk of the tree reveal an active imagination at work when it comes to picturing hellish detail. Here at Cranborne, though, the tree is shown to spring from the head of a female figure, painted in such painstakingly laboured detail that suspicion is immediately aroused about its authenticity.

By this I mean that although the overall shape and presentation of the figure is probably more or less what the medieval painter intended, this section of the painting nevertheless strikes me as the most likely of all to have been falsified by the repainting Tristram spoke of. The costume details – the pillbox hat and veil in particular – are right for the period, but the facial expression of the woman, the elaborate detail on the draped bodice of her robe, and the stiffly mannered treatment of her left arm and hand, grasping one of the tree-branches, cast doubt on the restorer’s understanding of the subject. The amateurishly insistent lines of the painting contribute to the feeling that all is not right with this; medieval church painters often employed far more subtlety than they are generally credited with, but there is none here.

Insofar as we can trust it, then, this is an interesting treatment of the Seven Deadly Sins. As elsewhere, it is paired in the church with a painting of the Seven Works of Mercy, which I hope will be here soon. A fragmentary Three Living and Three Dead and an equally fragmentary St Christopher also remain in the church.

† in page heading = Diocese