Hemblington, Norfolk (†Norwich) C.15

St Christopher

Only the St Christopher at Shorwell on the Isle of Wight can rival this example for fullness of detail. In fact the Hemblington St Christopher might once have had included even more incidents from Christopher’s life than Shorwell – much detail is missing from the left-hand side of the painting (i.e. the left bank of the river through which the saint wades). On this bank, at the level of Christopher’s right shoulder (main picture, left), is what looks like a substantial building, possibly the palace of the ‘king of the Cananees’, where Christopher began his quest for the greatest prince in the world, according to Caxton’s edition of his story from the Golden Legend. A figure might be entering the building at the right, but the details are very hard to see.

Below this at the right are more scenes of Christopher’s life before his meeting with the Christ Child, the clearest and most significant of which is his meeting with the Devil (detail, right). Christopher stands at the right, holding his staff and gesturing towards one of two horses. The second horse, further left, is saddled and ready, and behind it stands the Devil. His facial features are rudimentary and hard to see against the background, but his pointed ears and what might be a pointed hat should identify him. The scene below, now too faint for identification might have shown the Devil and Christopher coming upon the wayside Cross.

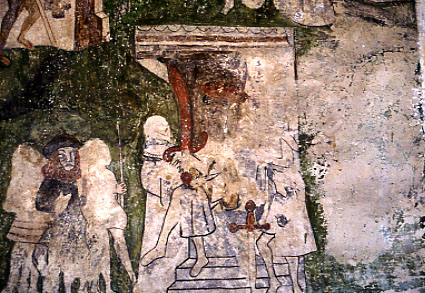

The narrative continues at the right-hand side of the painting, where it reads from bottom to top. In the bottom left-hand corner, Christopher, still seeking the ‘grettest prince that was in the world’, meets Dagarus, prince of Lycye (detail, below left). The king sits on a canopied throne mounted on a stepped plinth. He holds a huge red scimitar, and the painter has made his face huge, dark and monstrous (“Thou art rightfully called Dagarus for thou are the deth of the world, and felaw of the deuyl…”). His crossed legs also proclaim his status as a pagan tyrant; although some kings of old, like the Biblical David, might be shown seated cross-legged, the posture was also used to signify an evil pagan ruler, a fellow of the Devil. Christopher, who by this stage of the story has an ample reddish beard, stands to the left, guarded by the ‘two knights’ of Caxton’s account.

Further stages in the story continue above, including a scene taking place in what is probably Christopher’s prison cell (detail below right). Christopher, bearded still and wearing his hat, is at the left of the divided space with a female figure beside him. This must be one of the two women, Vysena and Aquylene, sent by Dagarus to seduce Christopher from the Christian faith. A blurred dark area to the right of her might have shown the second woman behind, and at the far right beyond the divide, a jailer goes out carrying what looks like a lantern.

According to Caxton’s account, after Christopher had converted them, Vysena and Aquylene pulled down the idols worshipped by Dagarus and his people, but this incident does not appear, although the women are shown with Christopher, identifiable by his red beard, confronting the seated Dagarus again at the far right (main photograph).

The two women appear a third time in one of the most interesting incidents of all, painted directly above the prison scene and shown in detail at the right. Several men operate a winch-like mechanism evidently constructed from the trunk of a lopped tree and ropes, while Aquylene and Vysena stand, stripped to the waist and hands clasped in prayer, beyond them. Aquylene, who was hanged, is, I think, the figure at the right, and from the tilt of her body it looks as if the mechanism has already lifted her from the ground. There is no obvious sign of the ‘ryght grete and heuy stone’ that was hanged at her feet according to the Golden Legend account (link above). Vysena’s burning and final beheading are not shown, and subsequent scenes deal with Christopher’s own fate.

To the right of the hanging of Aquylene, he is shown beaten by two torturers pictured left here; if the painter was using Caxton’s account, he has chosen to interpret the ‘roddes of yron’ specified there as heavy flail-like implements. Christopher still wears his hat, essential for identification of him in the many and various incidents here.

Christopher’s torments continue above this, with the attempt to shoot him with arrows (detail, below right). As in Caxton’s version of the story, the attempt fails miserably, with arrows deflected in all directions. Part of a kneeling figure is visible at the top of the scene, and this is Dagarus, kneeling before Christopher’s lifeless body (detail, below left) Christopher’s head has been severed, and lies beside his body. To the left, a man in a close-fitting hood must be the executioner. It is difficult to be sure, but Dagarus’s kneeling posture suggests that, having been struck in the eye by one of the arrows, he has followed Christopher’s instructions for healing it:

And the kyng thenne toke a lytyl of his [Christopher’s] blood, and leyde it on his eye, and sayde “In the name of god and of Seynt Christofre”, and was anon heled. Thenne the kyng byleved in God and gaf commaundement that yf ony persone blamed God or Seynt Christofer he shold anon be sleyne with the swerd…

There are a few other scenes here, but most are very unclear and simply involve Christopher standing again before Dagarus. The Hemblington painter has followed the story as narrated by Caxton very closely, although this does not mean that he used it directly as a source – accounts of Christopher’s life and fortunes must have circulated widely in manuscript before Caxton’s day. Some of the scenes – Dagarus’s repentance, the appearance of Aquylene and Vysena – are very rare indeed, and certainly unique in English wallpainting.

Website for Hemblington church

† in page heading = Diocese