Stoke-by-Clare, Suffolk (†St Edmundsbury & Ipswich), 1553-1558

Doom

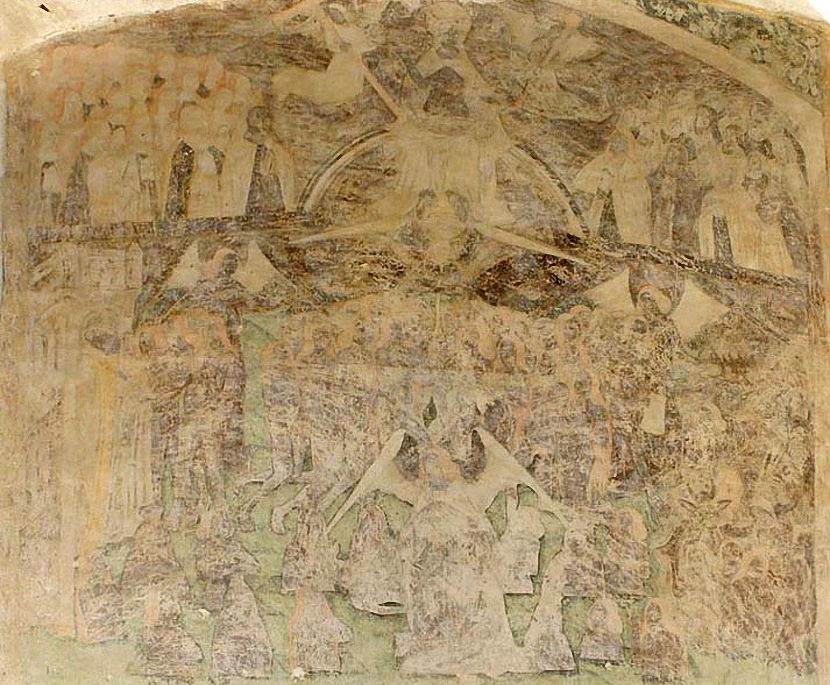

This extraordinary Doom, a very accomplished painting, is also a document for the English Reformation. It was painted during the reign of Mary 1, and is part of the Catholic reaction presided over by the queen herself. It was, needless to say, whitewashed over later. Its original location, the Lady Chapel, is now the organ chamber, and the cramped space and proximity of the organ pipes make it exceptionally difficult to photograph clearly.

Much about the iconography is unchanged since the Middle Ages, but along with a general concern for more precise symmetry in the arrangement of figures (particularly evident in the placing of the assisting angels with their sail-like wings), there is a distinct horizontal division between the realm of God and the saints in heaven, and the apocalyptic events taking place on earth. Flanking the Judging Christ, who is seated on a rainbow in standard fashion, the Virgin Mary is shown leading a group of female saints at the left, with a corresponding group of male saints, probably led by John the Evangelist, at the right. Immediately below Christ’s feet, where rays of light shine to right and left, an angel blows a trumpet which points directly downwards, across the heads of a group of kneeling figures. This detail, in the top right-hand corner of the photograph at the left, is hard to see, but it is evidence of an improved understanding of linear perspective since the Middle Ages. At the extreme left though, the apartments of Heaven show that the painter’s mastery of this is not yet total.

In the gateway of Heaven, St Peter, easily located by the bright yellow border of his cope, welcomes a group of the Saved, while at the right an angel assists the still-rising dead.

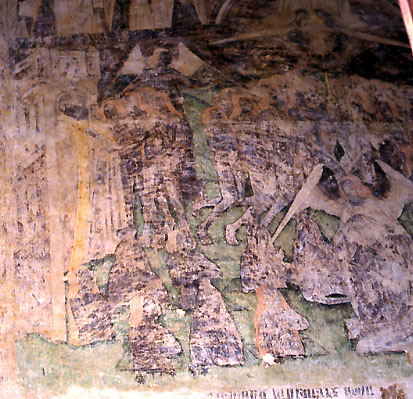

The opposite side of the painting, to the right of the centrally-placed angel, is devoted as usual to details of Hell and its inhabitants old and new. The largest and most prominent figure here, near the left-hand edge (photo, below right), is a devil, possibly Satan himself.

This devil’s horns form a lopsided crescent moon shape on top of his head, with his pointed ears showing below it. These ears have a feline appearance, and indeed the entire face has a cat-like aspect, with what look like slanted eyes, a snub nose, and perhaps even whiskers, although it is hard to be sure whether these are meaningful details or accidental marks on the paint.

The devil’s right arm clasps a human figure – probably a woman, although again it is hard to be sure, and what appears to be an elbow-length frilled sleeve on this arm is in fact a folded wing. To the right is another wing, this one extended horizontally, on the devil’s left shoulder. Lower down, another figure has the (very unmedieval) peach-coloured hair found on almost all the figures in the painting. In her case this is long – long enough to confirm her as a woman. In fact there are on the face of it a great many women here, but it is impossible to say what, if anything, this signifies.

There was once a Benedictine Priory at nearby Clare. In 1415, having moved to Stoke, it became a college of priests, and its last Dean was Matthew Parker, later to become Archbishop of Canterbury on the accession of Elizabeth I. As Elizabethan reformers went, Parker was a moderate, but what he would have thought of this painting is a matter for conjecture. It was prudently whitewashed out sometime after Mary’s death, and the area overpainted with texts, one of which, the Ten Commandments (ordered to be displayed prominently in churches at the Reformation) still survives in part below the painting – the tenth Commandment, proscribing covetousness, can with patience still be made out on the wall, e.g. ‘…his maid, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor anything that is his’.

The paint surface bears the marks of energetic scrubbing, possibly at the Reformation, possibly when it was cleaned in around 1950. It is almost certainly the last Doom to be painted in England, and certainly the only Marian example to survive. The page for the painting of Moses with the Ten Commandments at Stokesay in Shropshire has more details about the English Reformation and its attitude to images, and might be useful for comparison.