Wenhaston, Suffolk (†St Edmundsbury & Ipswich) c.1480

Doom (Painted on Boards)

This very large Doom is not technically a wall painting – it is painted on boards – but the whole painting was originally set under the chancel arch in the standard position. It is generally credited to a monk of nearby Blythburgh, presumably from the Augustinian Priory there¹. The position of the Rood-group remains outlined against it; unusually, this seems to have been attached to the boards (the holes for nails can still be seen) rather than simply being set up separately across the opening of the arch.

Because of this, the judging Christ on the rainbow sits at the top of the painting, but off-centre to the left. He holds a scroll in his right hand, and the words ‘Venite, benedicte’ (as at South Leigh) were once visible on it. The rayed Sun appears just above it, and a second scroll (‘Discedite, mal-edicte’) appears beside John the Baptist, kneeling with the Virgin at the far right. Faint traces of a crescent Moon are just visible above this scroll.

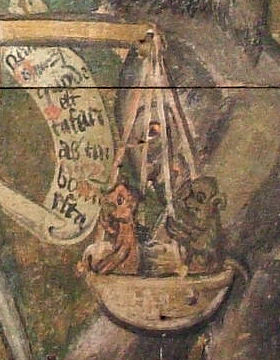

Below, the drama proceeds. Immediately below Christ and the cross-bar of the Rood outline, four of the Saved, a king, a pope, a cardinal and a queen, identifiable by their headgear but otherwise naked, are met by St Peter, in full pontifical vestments including Tiara, holding his key, while to the right of the upright of the cross-outline (detail, left), the Weighing of Souls is taking place. St Michael has a white robe and red cloak, instead of the armour he sometimes wears in this scene.

There is a tiny kneeling soul in the left-hand pan of the balance, and a large black devil with a face on his abdomen is trying to weigh down that opposite with, among other things, an inscribed scroll no doubt detailing sins committed. It is hard to read, but is reminiscent of the inscribed scrolls thrust at a dying man by devils in woodcuts in the Ars Moriendi². Two small devilish creatures, one of them greenish, perhaps for Envy, sit in the scale-pan trying to make up the weight.

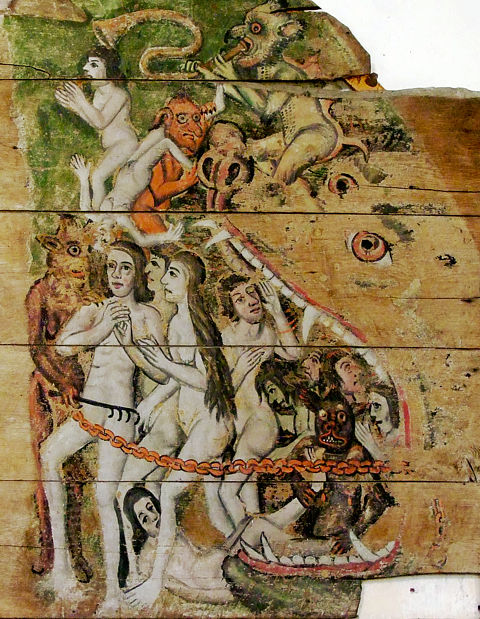

To the right of the Weighing is the Mouth of Hell (below right), literally painted as usual as a monstrous sea-creature. There are damned souls inside and various devils; a red one carries off a woman upside down on his back, a horribly grimacing black one sits in the Hell-mouth hauling another woman in by her leg. Another perches on top of the Mouth, blowing a curved horn.

Above all this (main picture), two souls in prayerful attitudes, one still hooded in a shroud, wait to proceed in one direction or the other. Diagonally opposite, at the lower far left beyond St Peter, is Heaven, with several small windows shown; one saved soul is at the door and another climbs the stairs to the destroyed upper part. Heaven is quite frequently shown as a building (Broughton, Buckinghamshire, Gt.Harrowden, Marston Moreteyne, South Leigh), but glimpses of the interior, as here, are very rare, and I will include a close-up detail of it at a future update.

The text painted underneath is curious. It is not contemporary with the Doom and must have been added some time after the Protestant Reformation, perhaps at around the time of the Second Act of Uniformity of 1552. It is in English and is part of Romans 13:1-4, but which translation of the Bible it comes from has never (so far as I know) been discovered. It reads:

‘Let every soule submit him selfe unto the authorytye of the hygher powers for there is no power but of God the Powers that be are ordeyend of God, but they that rest* or are againste the ordinaunce of God shall receyve to them selves utter damnacion. For rulers are not fearefull to them that do good But to them that do evyll for he is the mynister of God.’³

Although it is not absolutely clear whether the painting was visible when the text was added (it was covered with whitewash when it was found in 1889), it seems almost certain that it was. The warning about political dissent, cleverly presented in conjunction with the old and familiar iconography of ultimate salvation or damnation, is at any rate clear enough.

Website for Wenhaston church

The Wenhaston Doom: A Biography of a Sixteenth-Century Panel Painting (PDF)

¹A daughter house (Augustinian canons) of St Osyth’s Abbey – “The house was small with rarely more than 4 canons, and although the benefactions were considerable, the revenues were surprisingly small”, English Medieval Monasteries: A summary – Roy Midmer, Heinemann, 1979, p.71

²e.g. as in Eamon Duffy, The Strippping of the Altars, Yale, 1992, Pls. 117-119

³As transcribed in the leaflet in the church

*Perhaps “resist” was intended.