Stokesay, Shropshire (†Hereford) Later C.16/?C.17

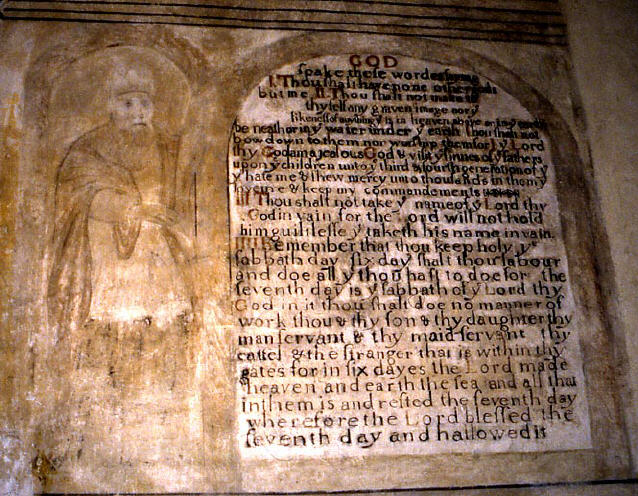

Moses(?) with the Ten Commandments

In date, the latest painting on the site, and thus not strictly medieval. It was made sometime after the Protestant Reformation in the mid 16th century, and since the church was largely rebuilt a century after that, it could be a very late example. But I include it as evidence of the not always clear-cut attitude to painted representations in the Reformation church. Whereas virtually no subject or personage from the Christian New Testament was countenanced, on the surviving evidence an exception seems to have been made for some important figures from the Jewish Bible or Old Testament, notably Moses and Aaron. In the case of Moses, this is presumably because of his unique position as recipient of the Tables of the Law, with the Ten Commandments. Tudor monarchs, not least Elizabeth 1, liked to think of themselves as heirs of Moses, the deliverer from exile and false doctrine.

We see here, I think, the Patriarch Moses himself (left of picture). He holds what seems to be a flaming torch, possibly a brand from Burning Bush, but in any case no doubt intended metaphorically as the Light of Truth. The painted text framed in the arched tabernacle beside him, with its variable character size and generally cramped appearance, is not a very distinguished example of painted script, but it is evidence of the rejection of the Gothic lettering of the Middle Ages in favour of the new italic forms. The new style had the virtue of a readable clarity not always shared by Gothic script. The remaining Commandments¹ (the first five are shown here) are also painted in the church in the same way, but rather more expertly, although the figure standing beside them is barely visible and impossible to identify. Hans Holbein’s woodcut images and texts from the Old Testament² were published in various editions between 1538 and 1549, and it is possible that they had some distant influence on this painting – the Moses here faintly recalls some aspects of Holbein’s.

The text of the Commandments is taken not from the Bible (Exodus 20: 1-17), but almost certainly from the English Prayer Book, probably the Second Book of Common Prayer of 1552. Although a few other painted Commandments have survived, the Stokesay examples are the only ones known to me in the English church to combine image and text in this way.

¹ Canon Law 82 (its precise date eludes me, but it may belong to the late Tudor miscellaneous legislation of 1603-4 about the ordering of churches) required the Commandments to be clearly displayed ‘at the East End’ of churches. The Stokesay paintings are in the nave, on the south and north walls, as are some other early painted Commandments in the English Church. But some English churches were setting up the painted Commandments above the chancel arch, sometimes obliterating existing painting there, from the middle of the 16th century onwards.

² Images from the Old Testament (Historiarum Veteris Testamenti Icones), Hans Holbein, ed. M. Marqusee, Paddington Press, 1976

† in page heading = Diocese