Launcells, Cornwall (†Truro) C.17

The Sacrifice of Isaac

The central part of this 17th century painting is shown to the right. Abraham, in a voluminous tunic, cloak and red hose, stands centrally. His right arm and hand, which once held a sword or knife, have virtually gone, but with his left he holds down the neck of his son Isaac, who kneels, wrists bound, at the right before a brick-built altar. Kindling, painted in red, perhaps to imply that it is already alight, is on the altar for the ‘burnt offering’ demanded by God in Genesis 22:2.

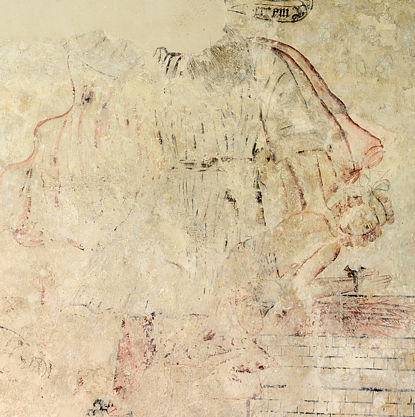

The Genesis story is closely followed by the painter, and there is much accompanying detail. Above Abraham, the ‘angel of the Lord’ (photo below), who called out to him to stay his hand, flies in from the left, damaged, but identifiable by its rather bat-like extended wings, bare feet and red-painted loose draperies.

A similarly clad angel at the right holds a serpentine scroll with an inscription, and there is painted illusionistic architecture, with some distinctive Mannerist features of the period, beyond at the far right. The ram caught in a thicket, substitute sacrifice for Isaac, is also here (below right), faint now, but probably once one of the more successfully executed details.

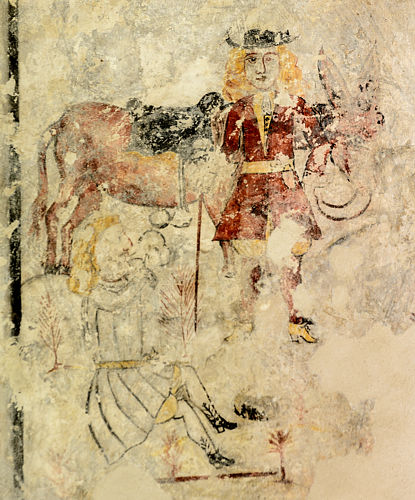

The various component parts of the painting are in fact extremely variable in quality. Abraham himself is a well-executed, fairly imposing figure, a tragic hero of the English neoclassical stage rather than the amorphously draped patriarch of medieval painting. Isaac is little more than a wooden marionette, but he is not to be compared with the ‘two young men’ who accompanied Abraham and Isaac to the mountain in Genesis 22:3 and who are painted here with quite stunning incompetence.

The ass, by far the most successfully painted detail, stands at the top, facing right horizontally across the space. In front, posing in short red tunic, yellow breeches, yellow high-heeled shoes and a low-crowned and wide-brimmed black hat, is one of Abraham’s attendants. The other is sitting on the ground below, drinking from a wineskin. He is dressed in clothes similar to those of his companion, but with distinctive black boots featuring high lacing or, possibly, patterned hose. The costumes, needless to say, belong to late Tudor or early Stuart England rather than Abrahamic times.

At the very top of this large painting is the vault of Heaven, painted to fit within an arched space on, unusually, the west wall of the church. There is a rayed sun-emblem here, more angels, and clouds, but all is now very faint.

At the bottom of the painting, though, is an inscription, possibly added later, but I suspect contemporary with the painting itself. Only a few words – ‘crucified’, ‘Christians not…’, ‘only for the…’ are really clear, but there is enough to suggest that this is not a quotation from the Bible. Reformation England saw the publication of a great number of commentaries on, or paraphrases of, the Bible, along with many polemical works defending or deploring the institution of the Reformed religion.This inscription probably comes from such a source, in all likelihood a typological work drawing parallels between the Crucifixion and its foreshadowing in the obedience of Abraham and his son. There is more on biblical typology, and a link to the Internet Biblia Pauperum, on the Genesis contents page.

![Sacrifice of Isaac, Launcells, detail, typological[?] inscription](images/launcells-5.jpg)

When this painting was made, Launcells may have been a royalist stronghold, since the letter of thanks sent by Charles I in 1643 to his loyal Cornish subjects is painted on the south wall of the church, and some of it is still readably clear beneath later plaster. The Abraham and Isaac painting is certainly very variable in terms of quality, possibly because a master and apprentices shared the work, but it is interesting as a survival from a period when the question of what, legitimately, might or might not appear as an image on a church wall was being actively debated. Representations of patriarchs such as Moses (as at Stokesay) and Abraham, as here, evidently remained acceptable.

You can see a 360° panoramic tour of the interior of the church here.

Website for St Swithin's Church, Launcells

† in page heading = Diocese

Photos © Roy Reed 2019