Pickering, N Yorkshire (†York) C.15

Passion Cycle

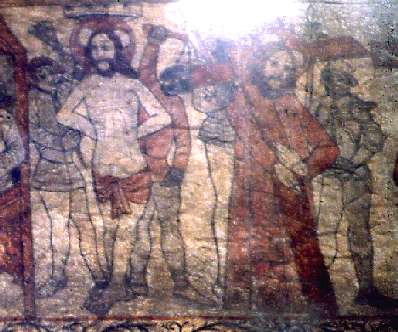

On the south wall at Pickering, this Passion Cycle is painted to the right (west) of the Seven Works of Mercy. It can be hard to see where one subject ends and the other begins – part of the priest officiating at the Burial of the Dead from the Seven Works is visible at the extreme left of the photograph. Immediately to the right of him, the Passion Cycle begins with a highly compressed scene of the Betrayal and Arrest of Christ (left, below).

Christ, painted with a very large lobed halo similar to that in the Trinity at Boughton Aluph in Kent, is in the centre of the scene, restoring the ear of the High Priest’s servant, Malchus¹, who has fallen to the ground below, still holding the lantern he traditionally carries. Beyond at the right, Peter, who cut off Malchus’s ear, is shown sheathing his sword. Soldiers surround the group, one of them grasping Christ by the right arm. Between the soldier and Christ is the head of a bearded man, inclined confidentially on Christ’s right shoulder. This is, I think, Judas (detail, left below); significantly, among the group of disciples and soldiers shown behind Peter and Christ, he is the only one with neither helmet nor halo.

After a very irregular black dividing line (nor necessarily original) a scene of Christ before Pilate follows, with Pilate seated on a canopied throne, holding a staff of office. Silhouetted against the side of the throne is something that might be the jug and basin Pilate used to wash his hands, but it is very hard to be sure. For one thing, I suspect that there are several pentimenti – examples of the artist’s changes of mind about the position of figures – in these scenes. Pilate’s feet, for example, seem oddly positioned.

The following scene is the Flagellation (right), with Christ bound to a pillar (the elaborate capital shows at the top, above his head) and flogged by two men. Immediately to the right, the scene becomes the Road to Calvary, with Christ carrying the Cross, escorted by two men, the one at the right a soldier in 15th century armour. This man apparently holds a staff with a decorated fleur-de-lys style top, perhaps to identify him as a centurion.

At the right beyond, and pictured below, the story continues to the Burial. On the left is the Crucifixion itself, with Mary and John flanking the Cross, and the title – the mocking description set up above the crucified Christ – painted as a scroll and clearly visible. In the centre a bearded man, probably Joseph of Arimathea, lifts Christ from the Cross while another removes the nails with very long pincers. The Burial, at the right, is one of the most detailed examples of the subject in the English Church. Two women are present, along with the youthful, beardless figure of John the Apostle at the left, by the top end of the (wooden?) coffin. Another Apostle further right cranes his neck to watch the standing figure of Joseph of Arimathea wrapping Christ’s feet in a winding-sheet.

In a spandrel directly below the burial is the Harrowing of Hell, a scene of great interest The shaggy curled hair of this Hell-creature is particularly finely painted, as are its great black teeth. At the far left of the scene, rays of light break from clouds, illuminating Christ, who stands at the Mouth of Hell grasping Adam by the wrist and holding a Cross. Adam, for his part, still holds the apple, a detail occasionally found in medieval art generally, but quite possibly unique in English wall painting. Eve, her hair loose, is behind Adam, and a bearded man behind her may be John the Baptist Other figures follow in turn, while two extremely ugly but now impotent devils, intended I think as cockatrices/basilisks, stand watching.

But the most remarkable feature of all here is the apparent censorship. Adam, Eve and the other visible figures coming, naked, out of Hell have large discs superimposed on their genital area. Since medieval painters (as in the Harrowing of Hell at North Cove) could always find ways around the problem of full-frontal nudity – usually by careful arrangement of legs or by simply leaving out what is between them altogether – this detail seems to demand some kind of symbolic interpretation. Perhaps it implies that since in Heaven they neither marry nor are given in marriage, and fornication is fairly obviously ruled out as well, genitalia are redundant in the transfigured flesh now raised incorruptible, and can be appropriately replaced by circles, symbolising eternity and perfection. If this is true I know of no other example of its being signified in this way. Another possibility of course is that these are distortions introduced by the considerable restoration the Pickering paintings have undergone, but in this case I doubt it.

In the spandrel to the left (east) of that showing the Harrowing of Hell and thus directly below the Betrayal/Arrest in Gethsemane is the Resurrection, a fine and dignified painting in which Christ stands poised on the edge of a stone sarcophagus, right hand blessing, holding the Vexillum, and flanked by two angels. Two of the soldiers guarding the tomb are present, one behind Christ’s right shoulder, the other in a reclining attitude and probably asleep, to the right of the sarcophagus.

There is one final scene, the Ascension, and it has been misidentified in the past as the Death of the Virgin (a series dealing with the Burial, Assumption and Coronation of the Virgin is elsewhere in the church, and will be on this site soon). The Ascension is painted above the rest of the Cycle², in the space between two clerestory windows at the west end of the south wall. Six Apostles are shown standing in a row, Peter in the centre holding the keys and Andrew with his saltire cross second left. The two figures on either side of Peter may be James the Great and James the Less. The traditional attribute of the latter is a fuller’s club, and one of these figures (second right) holds a short baton or rod over his shoulder. None of the fuller’s clubs I have seen elsewhere in medieval art much resemble this, although such things might well have varied in design from region to region.

The man at the far right is probably St John, and the object at the top centre of the painting, above Peter’s head, is perplexing. What remains of the detail is very unclear and only part of it shows in the large photograph, but I think it identifies the subject. If I am right, this is Christ’s naked foot (right), about to disappear into Heaven, as in most painted Ascensions of the period (the best comparison on the site is with North Cove) and here, with Christ appropriately about to vanish into the roof space and the sky beyond, this remarkable Passion Cycle ends.

The Pickering Martyrdoms of St Edmund and St Catherine, St Christopher and the fully reorganised Seven Works of Mercy, with new photographs and text, are also on the site.

Website for SS Peter & Paul, Pickering

¹ Named only in John 18: 10

² Conversely, the Resurrection and Harrowing of Hell are in a lower tier, below the main part of the Cycle. It is easy enough to find symbolic meaning here, but the arrangement might simply have been dictated by considerations of space