Gussage St Andrew, Dorset (†Salisbury [Sarum]) C.13

Passion Cycle

Surviving 13th century Passion Cycles are rare, and the best comparison on this site is probably with Fairstead in Essex. Some scenes at Gussage are fairly clear, others are identifiable but hard to make out, and others still are unidentifiable now.

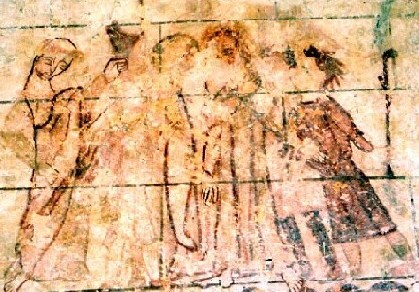

The cycle was uncovered in 1950 and has been expertly restored by Eve Baker. The story begins in the upper tier at the left. Here (left) Christ stands centrally, his visible left hand extended in a gesture of resignation. Pilate (he is more likely, although this may conceivably be Herod) sits at the left, on an throne with a diamond-patterned cushion. The small figure at the right, with a hooded tunic, is probably a guard or torturer. Pilate’s legs are crossed, usually, although not invariably, the sign of a tyrant in this period.

Following this is the Betrayal (right), a particularly successful example of a well-organised group of figures. At the far left is Peter, identifiable by his tonsure, who holds a lantern. The faint figure to the right of Peter is Malchus, the High Priest’s servant whose ear Peter cut off (Peter’s sword, held in his right hand, is just visible). Next right comes Judas, in the act of embracing Christ, who stands facing outwards. The other two figures at the far right are Pilate’s men, about to seize and arrest Christ The figure at the extreme right, who holds what looks like a scourge, has the wild hair so common in ‘bad’ characters in this narrative.

There may have been another very narrow scene next, but it is hard to guess what it may have been.

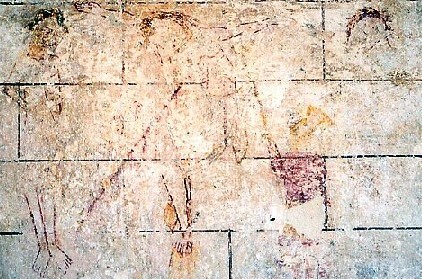

At the left below this and shown at the left here is the rarest scene in the Cycle, the Suicide of Judas, one of only three in England known to me (the others are at Breamore (where there is further discussion of the way this subject was depicted in the Middle Ages) and Slapton), and the only one integrated within an existing Passion Cycle.

Judas’s figure is badly damaged, but his dangling feet and most of his legs are clear, as is one hand, part of another, and the tree from which he hangs. Since the Biblical account makes it clear that Judas’s remorse followed more or less immediately after the betrayal, the subject is presented at Gussage at a logical point in the narrative. The scene must have been very striking indeed when it was first painted.

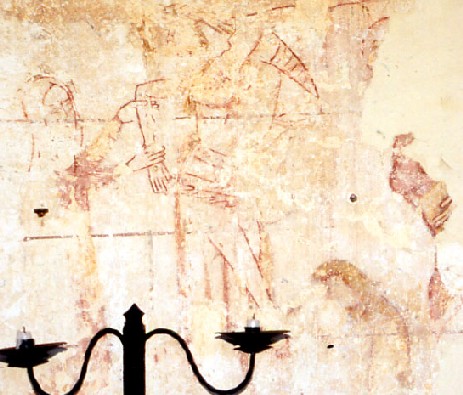

The next scene (right) is in all probability the Crowning with Thorns, since Christ appears to be seated, hands patiently crossed in his lap. Two figures are visible on either side of him, each reaching upwards towards his head, but beyond that, what remains of this is obscure. Another scene, showing a face which may be Christ’s own, follows, but the detail is too obscure for firm identification.

The action now passes to the lower tier, where the first scene at the left (shown below left) is the Road to Calvary. The faint Cross is held over Christ’s shoulder, and his face above it is turned as he looks back over his shoulder. To his right, a much smaller figure, who wears a red and yellow robe and may carry a hammer, precedes him.

The next scene is the climactic event, the Crucifixion (below left). Christ is central again, and there are faint remains of the two thieves on either side. At the right, a very faint figure of Longinus, wearing a yellow Roman helmet, pierces Christ’s side. Stephaton on the left is effectively gone, but the lance on which he held up the sponge is still visible as a dark slanting line. There are traces of another figure, perhaps St John, at the far right.

After this comes the Deposition, shown below left, with a female figure, almost certainly the Virgin Mary, at the right. Below, by Christ’s feet, another figure, probably Mary Magdalene, is grasping Christ by the forearm and helping to remove him from the Cross. The details are confusing, but there seems to be another figure on the right of the Cross, possibly wearing a pointed conical hood with a pattern of horizontal lines on it. The conical shape may be something else, but this area is unclear now. Some other details farther to the right and including part of a hand, may be all that is left of a Resurrection, but the wall has been replastered in this area and all other details have gone. The only other visible fragment, on the far right of the area of replastered wall and not shown in the main picture, is, I think, the Entombment (below right).

The grave-faced figure on the right extends his hands in the manner of someone holding one end of something heavy such as a body in a winding-sheet, while his yellow-haired companion raises his right hand as if in sorrowful perplexity. The figures seem to be male, and may be Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus.

There is a long inscription below the Cycle. The leaflet in the church describes the inscriptions in the church in general terms as probably 17th century, but the painted masonry pattern on which the Passion Cycle is superimposed continues below the Cycle itself, suggesting that the inscription below may be intended to elucidate it, and thus be contemporary with it. It is admittedly very difficult to be certain, but from what little can be seen this looks like the very upright, narrow Gothic script of the High Middle Ages, rather than anything added in the 17th century.

At any rate it is a very fine and valuable example indeed. Tristram did not record it, and it certainly deserves to be better known.