Little Witchingham, Norfolk, (CCT*) C14

Passion Cycle

The Passion Cycle and other scenes – a row of Apostles at the top of the wall and a very large but much damaged St George and the Dragon on the far right, to the left of the window – are on the north wall.

The paintings here are masterly. They were discovered by the conservator and restorer Eve Baker (who is said to have climbed through a window to get in) when the church was virtually derelict in 1967. Unfortunately only a few scenes are really decipherable now.

The central tier has the clearest, and it begins at the west end (left) of the church with one or possibly two scenes, both very obscure and not shown here, which may be the Arrest in Gethsamene and the Agony in the Garden.

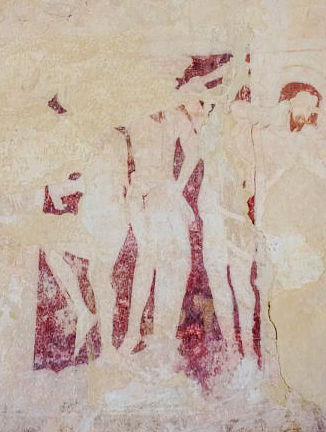

The clearer scenes begin with the Flagellation (over the North Door shown in the picture to the left) combined with the Buffeting and shown in the detail at the right. Christ seems to be the central figure here, and he is probably standing in front of the Pillar of the Scourging while torturers variously scourge him (the figure at the left is poised on one leg in the act of wielding a scourge) and press down the Crown of Thorns with clubs or staves, a detail sometimes seem in manuscript painting and the art of the Northern Renaissance.

The next scenes to the right are very fragmentary, but immediately right, after Christ before Caiaphas is probably the Road to Calvary; the one to the right of that must have been the Crucifixion and the remains of another scene, unidentifiable now.

Only the upper part of one scene, and the upper left part of the one to the right of it, is visible now. The figure with the halo at the far left is certainly Christ, and the figure to the right of him, wearing on his head what looks like a bishop’s mitre, is probably Caiaphas. The mitre would have been the nearest thing to the headgear of a High Priest of the Sanhedrin in the mind of an English medieval painter.

There are three other figures, all faint, but the one to the immediate right of Christ is a soldier wearing a helmet. The identification must remain uncertain, but on balance Caiaphas, rather than Pilate or Herod, seems the most likely figure to be confronting Christ here (medieval painters did not always follow in sequence the events of the Passion as narrated by one or another Gospel account). The central and lower parts of this scene have disappeared almost completely, but there is a suggestion of compartmentalised horizontal division, and there may once have been other scenes of Christ’s examination by the Jerusalem authorities here. At the far right is a haloed head which probably belongs to a scene of the Road to Calvary. It looks female, and may not have been the head of Christ – I suspect that this may be the Virgin, helping her Son to carry the Cross, a detail sometimes found in manuscript painting. Nothing else is left of the rest of this scene or of anything immediately to the right of it, where a scene of the Crucifixion was probably painted – certainly there is no sign of it elsewhere.

At the left above is the next clear, if now incomplete, scene, the Deposition, or Descent from the Cross, with a ladder and a figure climbing up it clearly visible. At least two other figures are detectable, on the left of the Cross – the Virgin Mary and St John are almost certainly there, along, perhaps, with Joseph of Arimathea and possibly Nicodemus. Christ’s forked beard, very common in Passion scenes of this date, shows well after Eve Baker’s restoration.

At the right is the Entombment of Christ, a rare survival in the English church. This example is obviously very obscure, but just enough restoration has been done to make the painting intelligible. The stooped figure with long red hair and beard is either Joseph of Arimathea or Nicodemus – I think probably the former – in the act of lowering Christ’s body into the tomb. Two corners of the rectangular classical sarcophagus, outlined in red, show the shape of this. At the left Christ’s head and upper body, raised on an incline as his feet are lowered, is faint but visible.

This scene ends immediately to the right of the figure lowering Christ into the tomb, and a plain vertical border can be seen dividing it from the next to the right, the Resurrection. This has now disappeared almost completely, but the roughly rectangular left-leaning shape immediately to the right of the vertical border is the slab covering the sarcophagus, now pushed away. It is very difficult to see on the photograph, and only a little more so in reality, but Christ’s right hand, extended and palm upwards, is held out across this slab. The rest of the Resurrection, apart from three stylised tree-branches at the upper right, is obscured, but part of something that looks like an angel’s wing and probably belonging to an angel standing behind the propped-up tomb slab can be seen crossing the vertical border obliquely to hover above Joseph of Arimathea/Nicodemus’s head. The remaining scenes are shown below.

At the left is the Harrowing of Hell, a very fine example of the subject, damaged as it is. Christ stands at the left, holding the banner-stave of the Vexillum or Banner of the Resurrection with the cross at the top of it showing to the left above his head. On the right, the great Mouth of Hell, with three huge teeth showing at the top, gapes open, spanning the entire length of the painting. The haloes of two figures about to emerge from Hell are visible; they may be Adam and Eve.

There were once probably more figures, or at least their heads, painted here, and enough of one of them, a bearded man looking out from the bottom right, was clear enough to be restored. He may be John the Baptist, but there are other candidates too among the righteous who died before the Atonement – Piers Plowman’s “Patriarkes and prophetes that in peyne liggen”.

The remaining scenes, the Appearance to Mary Magdalene and the Incredulity of Thomas, are below. I am not certain, but I think the scene at the right must be the remains of an Appearance to Mary Magdalene, now very seldom found in the English church. Christ stands at the right, again with the Banner of the Resurrection. His right arm and hand, only faintly visible, are extended above the now very vague shape of another figure (probably) kneeling, below. This must be Mary Magdalene, reaching out to touch her Master but being dissuaded – a very faded yellowish patch in the centre of the painting looks like her extended arm. The only other detectable detail is the at the left – the ghost of another of the stylised trees, with graceful S-curved trunks, which feature elsewhere in the Cycle.

In a rare surviving example of this scene (left) St Thomas kneels at the left, in front of a tree painted in the background. Unlike the other trees painted in this Cycle, this one is flourishing, with a crown of leaves issuing from the trunk and no bare branches below.

The Bible account, narrated only in John, of Christ’s appearance to the Apostles when ‘doubting’ Thomas was present [John 20:24-28], seems to imply (“the doors being shut”) that this event took place indoors. Also, according to the Bible, Christ’s words to Thomas in John 20:27 were enough to compel belief, and there is no account of any actual touching. But the painter has shown Christ guiding Thomas’s hand to the wound in his side, and the kneeling figure seems to be a bearded man, clinching the identification, I think. Thomas is holding something – one possibility is a book, since apocryphal writings, including an Acts of Thomas, a Gospel of Thomas and an Infancy Gospel of Thomas were all confidently attributed to him in the Medieval period.

This very fine and very rare post-Resurrection appearance is the final one in the Passion Cycle, but, as can be seen in the photograph on the first page, there are other paintings here, including three (remaining out of four) very fine roundels with Evangelist Symbols (forthcoming).

*CCT=The Churches Conservation Trust, successor to the Redundant Churches Fund