Brook, Kent (†Canterbury) c.1250

Infancy Cycle (chancel)

“…sit thou on my right hand, till I make thine enemies my footstool” ¹

As with the Passion Cycle at Brook, on-screen reproduction cannot take account of the scale of these very large paintings. The individual roundels are some 60cm in diameter, and they include some very rare scenes indeed. Some of the story is told in a series of roundels painted on the east wall of the chancel but the earliest episodes – i.e. those recounting the Nativity of Jesus, are on the south wall, where they follow, without a break a very damaged and incomplete series of the Life of the Virgin.

Virtually nothing is left of the first Nativity scene, the Appearance to the Shepherds. Following that, the Adoration of the Shepherds has been reduced to a few fragmentary but identifiable details, including the tightly swaddled infant Christ lying in a crib, but next in the sequence come several much clearer scenes involving the Magi. The first (right) shows their arrival before Herod’s palace. Three crowned figures on horseback approach the crenellated gate of a city. The central rider raises his arm in interrogation, and/or to indicate the now indecipherable guiding star. Within the gateway, a retainer-figure in a short tunic directs them inside.

In the next scene (left) the Magi meet Herod. He is the seated figure in a dark robe, his authority signified not only by his crown and sceptre, but also by his prominent footstool, a significant object both in itself and in the light of a later scene in the cycle (the Dispute with the Doctors, discussed below). The Magi stand respectfully at the left, the one nearest Herod with his hand raised to signify inquiry.

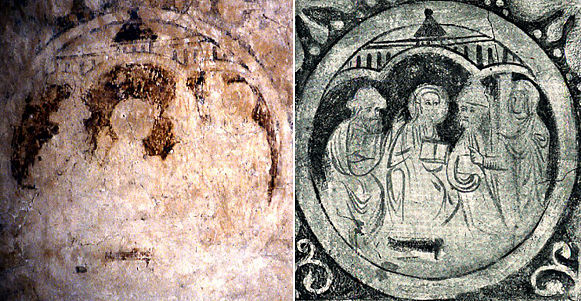

Two scenes follow this, a probable Dream of the Magi, now faded to near-invisibility, and a very faded, fragmentary but identifiable Presentation in the Temple. These are followed by the Dispute with the Doctors, (below left, with an old black-and-white drawing of it beside it**) of which only one other (and forthcoming) example, at Hardham in Sussex, remains in the English church². The drawing makes it clearer that the seated Christ is evidently the one with the footstool now, in an interesting and perceptive piece of symbolism. Within the roundel, the interior of the Temple is represented by a triple round-arched arcade with architectural detail above it, a kind of cupola or dome placed centrally, and a suggestion of high windows or, alternatively, distant buildings. As with the architecture of Jerusalem in the Passion Cycle at Great Tew, its appearance may even be based on first-hand experience, since Jerusalem was the ultimate destination for all medieval pilgrims.

Below this, Christ, identifiable by his round halo, is seated centrally, flanked by two figures in rabbinical headgear, the one to the (onlooker’s) left with hand raised and index finger extended. The faint figure standing at the right is the Virgin Mary, in search of her missing son. Below the figure of Christ, the footstool shows as a dark horizontal line (it was first identified by Tristram³), and comparison with Herod’s in the photograph above right will confirm that this is what it is. The inclusion in both scenes of this very ancient symbol of authority, divine and/or earthly, literal or metaphorical, is intriguing; perhaps its appearance in juxtaposed scenes beneath the feet of a murderous tyrant and those of the King of kings is a deliberate irony on the part of the painter. It would be rash to rule such subtleties out, especially in work of this quality.

There is one further scene on this south wall. Enough is left – part of a table with dishes, several figures, one with a halo, another a woman – to suggest that it may be the Marriage at Cana, but this is uncertain. The narrative then continues on the east wall (to the south of the window), where scenes are arranged in a rectangular panel as in the Passion Cycle. The first of these, (top tier, left) is totally obliterated, but that immediately following it and pictured at the left is a well-preserved Flight into Egypt (the apparently muddled chronology here reflects the fact that the painter is recounting incidents from at least two Gospels, Matthew and Luke, and in the case of the Marriage at Cana possibly John as well).

Joseph, at the right, leads the donkey on which Mary sits, holding the infant Jesus closely against her face and neck. The scene is faded now, but this must once have been a beautifully tender detail, even if the child is a little on the large side. The object at the extreme left is a stylised tree, very much of its period. Joseph at the right leads the donkey, a T-shaped staff with what look like bundles of possessions carried on it, over his shoulder.

The following two scenes are the rarest of all. The first, the Fall of the Idols (right), is entirely apocryphal, and along with many other Infancy legends emerges to account for the “silent years” in the Biblical narrative. According to the story, Mary, Joseph and the child entered the Egyptian city of Sotinen, where, in search of lodgings, they went into a pagan temple. Immediately the idols worshipped there (three hundred and fifty-five of them) fell down and shattered. Conversions to Christianity ensued.

Understandably, the Brook painter has chosen to show only one, representative, idol. Framed within what is probably intended as the portico of the temple, a sinister- looking creature with horns and a suggestion of bat-like wings falls head-first from a large plinth. The scene is exceptionally rare in English church art*, and only Hardham in Sussex has another. The legend comes from the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew and this link will take you to an online version of this rich collection of Infancy legends and traditions – including those of the Virgin as well as Christ.

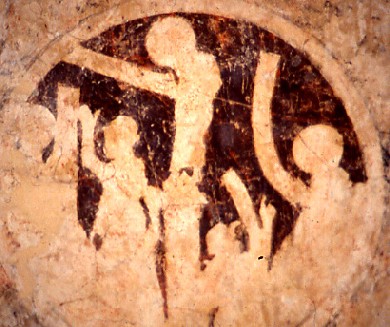

If the Fall of the Idols is uncommon, then the next scene, the Temptation in the Wilderness, (left) is now unique in England (the three other examples listed by Keyser, with the exception of the problematic Ashridge [footnote 2, below], have all been destroyed and were in any case only dubiously identified.)

In the centre, Christ stands on top of the pinnacle of the Temple, in the second of the three incidents that make up the Temptation story in Matthew 4:3-10. His right arm is extended and he holds a scroll, now indecipherable along with all the others in the scene. Below him and slightly to the left, a now very vague figure holds up an arm towards him, and it is clear enough that a conversation is taking place.

The other instances of the threefold Temptation are here too. At the far left of the roundel Christ, identifiable by his halo, appears again, with beyond him to the right another figure, presumably Satan, raising his right arm and hand, the thumb clearly visible. Logically this should be, and almost certainly is, the ‘stones into bread’ incident of Matthew 4: 3. Finally at the right of the roundel, Christ, his speech-scroll curving upwards, looks down at a figure shown in profile whose grotesquely hooked nose and raised, stabbing finger confirm him as Satan, and the episode as the third and final temptation in which Christ rejects the temporal kingdoms of the world and all their glory. I know of only one other example in Europe, in a 14th century Life of Christ at Lenz (Lantsch) in Switzerland. There, in a 14th century example, Christ, Satan, and the stones/bread are all clear, as is the Baptism of Christ preceding it at Lenz.

At Brook, the next scene (not shown here) has a figure, probably Christ, standing at the left and another, probably an angel at the right. There is also a suggestion of an arc in the sky above. Tristram suggested that this episode might represent the Baptism of Christ, or perhaps angels ministering to him after Satan’s departure. On the whole, I think the former, marking an end to the Infancy Cycle as normally understood is more likely, but not enough is left to be sure. At any rate, the narrative now moves forward into scenes of Christ’s earthly ministry, the Raising of Lazarus and the Raising of Jairus’s daughter, already on the site, and thereafter to the Passion Cycle, already linked on this page.

The Brook Infancy Cycle is certainly the most complete example of its kind in England, and the rarity of some of its scenes makes it very remarkable indeed. Other paintings in the church, most of them very badly damaged, include an Annunciation (very clear) and Visitation (less so), and I hope to include these here in due course.

¹ Luke 20: 42-43

² Another recorded by Keyser at Ashridge College in Buckinghamshire may or may not still be there. According to Keyser the entire 40-episode Life and Passion of Christ was “defaced” in 1880. CE Keyser, List of Buildings having mural decorations…, p.10 [See Bibliography]

³ Tristram II, p.511

* Although it is often found in French carving and painting. This may be because the Roman governor of Sotinen, Aphrodosius, was said to have been among the converts. He later travelled to France, so the story goes, and eventually became the first bishop of Béziers. E. Mâle, trs. D. Nussey, Religious Art in France: Thirteenth Century, London, 1913, p.217

** Drawing said to have been made in 1908, reproduced in Frank Kendon, Mural Paintings in English Churches during the Middle Ages, London, 1923. Whether this is is Kendon’s own drawing or not I do not know, but no picture credit is given.