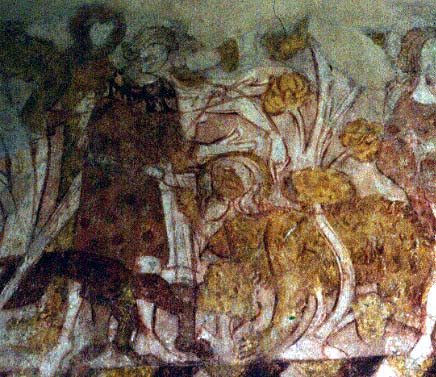

Old Idsworth, Hampshire (†Portsmouth) Early C.14

The Legend of the Hairy Anchorite

The complicated tale is difficult to condense, but the essentials are as follows:

The wealthy Earl of Beverley in Yorkshire, England, had two children, his son, called Jan, and a daughter, Colette. Like St Francis of Assisi, Jan decides one day to renounce his inheritance and the world, and leaves home to live a hermit’s life in the forest Colette his sister visits him one day to persuade him to return but he refuses, and she leaves after promising to visit more often. The Devil then appears to Jan in the form of an angel, as medieval devils often did, and tells him that in order to escape eternal damnation (for his vainglorious pride in his own piety) he must commit one of three sins – drunkeness, inchastity, or murder. Jan chooses drunkeness as the least heinous, and when Colette his sister revists him, asks her to bring wine with her next time. This she does, staying with him for his own safety while he drinks it. The wine and his inhibitions gone, Jan then rapes Colette, and buries her body. Sobriety eventually returns, and with it comes the temptation to despair at the number and magnitude of his sins, thus adding to an already grievous burden.

Instead, he travels to Rome to seek absolution from the Pope himself, but is discomfited to be told that no suitable penance can be fixed and he should instead return to England and seek the advice of the hermit John of Beverley. Back in England, Jan imposes his own penance, vowing to walk on all fours, drink only water, eat only grass, and not utter a word until a one-day old child tells him that God has forgiven him.

Dr Alan Deighton takes up the story:

“Seven years pass. Jan’s father has died and a new earl has been chosen. To celebrate the birth of his child, the earl goes hunting. Some hunters find Jan whom they take to be a new species of wild animal. He is captured and taken to the earl's court, where the new-born child absolves him, upon which the Bishop [sic] of Canterbury is brought to Beverley to hear Jan's confession.

He [Jan] then returns to Colette’s grave, opens it to discover his sister still alive and describing the joys of paradise which she has been experiencing in the company of angels since her murder. They go off together praising God and in search of the Bishop in order to receive the holy Sacrament.” ²

Comparison of the small black-and-white image at the right, taken from the original Dutch chapbook version of the tale, with the Idsworth painting clinches the identification of the subject, I think. It is the Legend of the Hairy Anchorite, alias Jan van Beverley. It has nothing to do with St Hubert or any other patron saint of hunters, and my earlier (if tentative) suggestion that this painting was more likely to be some unknown episode in the Life of St Hubert has taught me that Occam’s razor must be used with care.

This does not mean that there are no puzzles at Idsworth, because there are still many. There are, for example several intriguing parallels between the the story of Jan van Beverley the young aristocrat, what is known about the life of the hermit-saint John of Beverley (ob.721),¹ and the life of John the Baptist, part of whose painted story follows this one on the wall at Idsworth. The power of speech – being bereft of it, vowing not to use it, and recovering it, features in all three.

Here at the far left is a detail from the painting showing the the new young Earl of Beverley taking the hairy anchorite by the hand. His short, ‘pageboy’ hair testifies to his youth, and the richly embroidered yoke of his robe to his aristocratic status. A confusion of Johns and Jans seems to to have entered the story early, and the fact remains that the painted Legend is followed without a break by the taking of John the Baptist by two rather sketchily painted men (the distorted features so commonly found in medieval paintings of persecutors are nevertheless visible, at least in the larger detail on the page for Herod’s Feast). The story of John the Baptist continues there.

Website for St Hubert’s, Old Idsworth

*My grateful thanks are due to Fr. John Julian, OJN, through whose good offices I learned of the work of Dr Alan Deighton.

¹The Oxford Dictionary of Saints, ed. DH Farmer, (3rd edition) OUP has a useful entry for John of Beverley.

²[From an English version of the story in Historie van Jan van Beverley, translated from the original Dutch and provided by Dr Alan R Deighton, Professor of German and Director of the Centre for Medieval Studies at the University of Hull] This is a very rare case of a church’s dedication being changed to accord with an artefact (in this case, the painted story on the north wall) within it. The original dedication was to SSt Peter & Paul, and the present dedication to St Hubert dates only from the late 19th century. The painting was first discovered in 1864.

³[The wood engraving by an unknown engraver is taken from the original chapbook version of the story of Jan van Beverley published by Thomas van der Noot (Brussels, c.1510) and is not to be reproduced without permission]