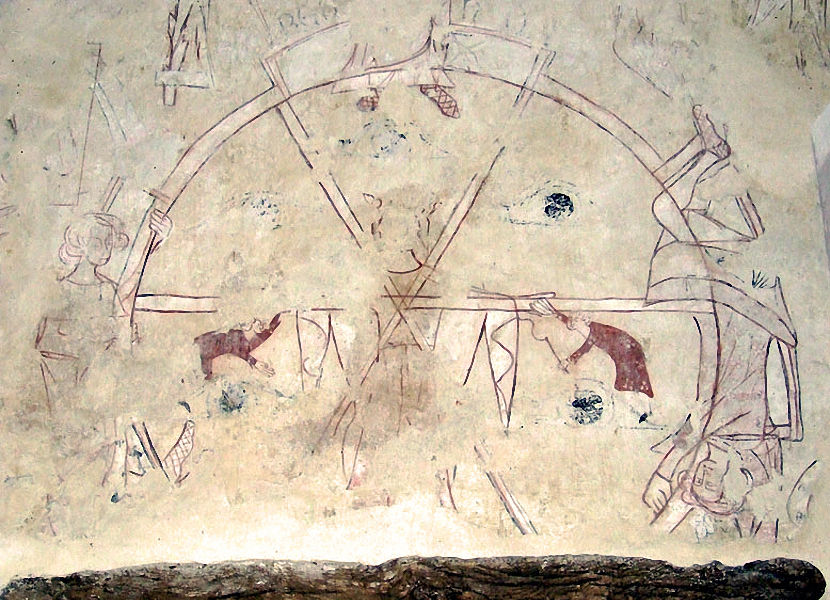

Ilketshall St Andrew, Suffolk (†St Edmundsbury & Ipswich) c.1330

The Wheel of Fortune

‘ O Fortuna velut luna statu variabilis, semper crescis aut decrescis…’

[O Fortune, changeable like the moon, ever waxing and waning…]

(13th century Goliardic song)

The Consolation of Philosophy, a 6th century work by Bœthius, was one of the most widely and consistently studied texts of the Middle Ages. King Alfred presided over a translation of part of it, as did Elizabeth 1. It would be hard to overestimate its importance for medieval thought. The best-known symbol associated with the central figure of the Consolation, Fortune, is of course the Wheel, and this example from Suffolk, discovered only in 2001, is one of only two certainly identified paintings of the subject in the English church. The photograph to the right shows what is left of the other, in Rochester Cathedral, although the Rochester example, dating from around 1245, is rather earlier.

The basic theme of the Wheel of Fortune is the unpredictable nature of human affairs. Fortune, usually although not invariably depicted as female, turns her wheel, and humankind must follow the rotation. The motion is however, circular, so a downturn in human affairs, whether on a personal, social, civic or global level must inevitably be followed by an upturn. The partly visible crowned figure sitting on top of the rim of the wheel at Ilketshall, who has, carefully spaced on either side of him, the inscribed Latin word Regno (I rule), must inevitably descend, another shown upside down at the right (and once possibly accompanied by an inscription Regnavi [I have ruled]) is already doing so, and a third at the left – Regnabo [I shall rule] is on his way up. Any fourth figure (sum sine Regno) at the bottom centre of the wheel would would have been lost in later restorations. Fortune stands in the centre, dressed in wide-sleeved 14th century garb with arms extended to turn the wheel. She apparently has helpers, in the form of two subsidiary (and far less competently painted) figures set in the horizontal centre of the wheel, the figure on the right possibly cranking some kind of handle. In addition to this, and also placed within the wheel are four almond-shaped details resembling, and perhaps intended for, eyes, in this case maybe the all-seeing eyes of God.

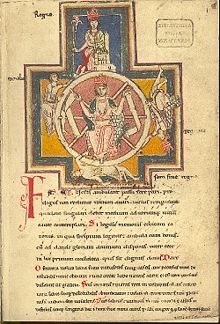

God, of course, is superior to Fortune and her vagaries, and these eyes (if that is what they are) may be there to render what is essentially a pagan idea acceptable in a Christian church in a remote rural area. Alternatively (and I think this is more likely) God may once have been shown separately, enthroned above the wheel, as he is in the manuscript illustration at the left, but 15th century alterations to the church mean that anything painted in this area has been lost To complicate mattters, further east (left) on the south wall are the remnants of a Doom, and some details – opening graves, for example, apparently belonging to this are still visible on the wall below the wooden supporting beam beneath the wheel. Certain aspects of this Doom also suggest the influence of manuscript painting, which seems to have been important at Ilketshall, and I will try to include some of the details from it, fragmentary as they are, at a future date. And on the north wall of the church there is another painting, equally mysterious in its way, showing a church or chapel, apparently quite deserted, with a draped altar laid up for Mass with chalice and paten.

The Wheel of Fortune was probably once fairly commonly found in English parish churches, but this is the only near-intact one known to me, apart from a fragment still visible at Old Weston in Northamptonshire. There are other wheels, but the dificulty lies in identifying them as wheels of fortune, as opposed to other, moralising, subjects painted in wheel-diagram form. This link will take you to a contemporary manuscript painting of the subject from the Holkham Bible. The Holkham bible, originally made for a Dominican friar and popular preacher, gets its name from what is now Holkham Hall in Norfolk, in whose library the Bible was originally housed. It may be pure coincidence that Holkham Hall is not far from Ilketshall, but it is intriguing all the same.

* This is a revised link to another copy of the image – scroll down the page until you reach the section on Chaucer’s language -the original direct link to the British Library image is apparently broken.

Photo: Wheel of Fortune, Rochester Cathedral © Roy Reed 2017