Swanbourne, Buckinghamshire (†Oxford) Late C.14/Early C.15

Allegory of the Penitent and Impenitent Soul

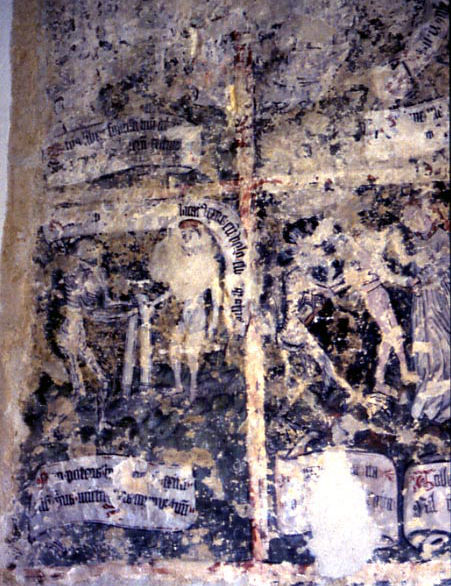

This very curious painting is complicated and elaborate even by the normal standards of medieval allegory. It is arranged in compartments and tiers and is a moralising narrative about the necessity for true penitence and the fate of those who die without it. Shown above is what remains of the highest tier. The first scene, to the left, has almost totally gone, but notes available in the church describe what was visible there in the 1870s. A female figure, probably symbolising the human soul and not specifically intended as a female person (the soul was usually spoken of as ‘she’) stood before an angel. A scroll below read (in Latin)‘ Because thou hast finally paid thy debt, I give thee leave to go’ [quia libera solvisti tuum debitum…do ergo tibi liberum exitum’]¹. Moving right, the next and final stage of this soul’s journey is damaged, but rather clearer. The soul now kneels before a figure identified by the notes as Christ; he has a red robe and traces remain of a halo which once showed as painted in green and gold. These are also the colours of the crown which he places on the kneeling soul’s head. To the right beyond and reduced to sketchiness now, another scene gave a view through windows into a chamber, presumably of Heaven, where angels and smaller figures probably representing the Blessed, were visible. In the second tier and shown here at the left is the next and clearest scene.

Here, Death, personified with the usual grim realism as a semi-skeletal figure retaining some skin, hair and teeth, presents a priest’s stole to another female soul-figure. The notes identify this stole as the mortal body, in allusion to the ‘body of this death’ of Romans 7:24. A scroll above the soul is virtually unreadable (the first word may be ‘Indicat’), but a scroll below is translated as ‘thou wilt not be able to make thy exit unless thou givest me thy body’ [‘non potest hic facere exitum…dederis corpus tuum’].

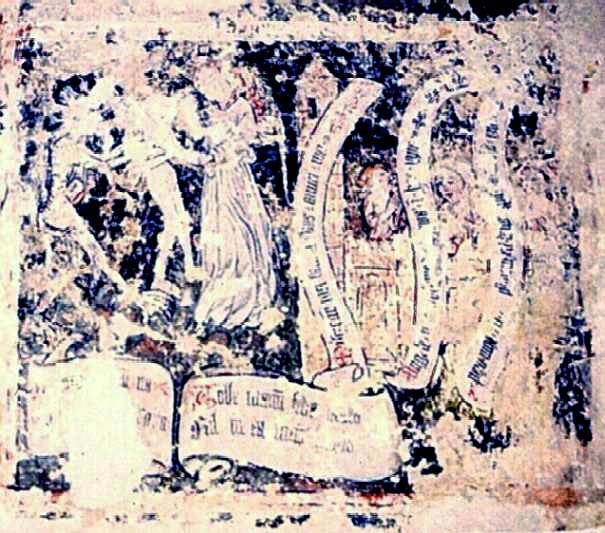

In the next scene to the right, partly visible here at the left and shown in full below, it becomes clear that this soul is destined for Purgatory as the angel and a devil struggle for possession of it. The devil has looped the priest’s stole around the soul’s neck and is pulling vigorously on it, while the angel at the right has taken the soul by the hand. Once again scrolls below guide the onlooker’s understanding. The page of the ‘open book’ scroll below the devil reads ‘Thou wilt not escape from me thus’ […Me sequebar (?) is tu in vita’]. The scroll on the right-hand page below the angel says ‘Take my hand, O foul corruption…[nil in ea vitis(?) habes]. The scene continues on the right with a depiction of souls in Purgatory, painted as a tall narrow tower flanked by a lower battlement. Three souls are visible, in prayerful attitudes and also with speech-scrolls. The first (from left) reads ‘Remember me, ye saints and you my friends’¹*, the second ‘angels, (remember us?) in this fire’ and the third ‘I hope soon to be in (Paradise?)’.

There is a third and lowest tier, but this is largely obliterated by a memorial tablet. According to the notes (which the writer admits are doubtful at this stage) a female figure emerges from a doorway with the stole around her. Death, attended by an evil spirit or demon, is taking the stole off. The figure laments ‘Wretched am I, to whom thou hast come so quickly/Thou has found me penitent from…?’. Death replies ‘No(?). Thou hast not paid thy debt worthily. Thou shalt give it however in the body of thy life’. A fragment of inscription reads ‘Timor mortis’², and then the evil spirit leads off the reluctant figure. Further fragmentary inscriptions, grouped around what the writer of the notes calls ‘three evil spirits rampant’ read ‘Thou hast merited for us…’, ‘the gift of eternal life…’, ‘Thou who are about to die dost deservedly fear to die since the penalty of death is so severe’. Finally, below the whole allegory is part of a motto or moralising conclusion in English – ‘Man liveth to die…in…a dream at his fate’.

The painting is obviously now obscure, and the notes from Records of Buckinghamshire in the framed form available in the church are now themselves faded and hard to decipher in parts. But the general drift is clear – this is an allegory contrasting the eventual fates of the Penitent and Impenitent soul respectively. At the top, a penitent soul has paid its debt of sin and is delivered, I think from a sojourn in Purgatory (‘Because thou hast finally paid thy debt…’) and not because the figure represents ‘the perfect man’ who goes straight to Heaven after death as the notes claim. Below is the fate of the Impenitent Soul, summoned by Death and destined either for Hell or for Purgatory (‘Because thou hast not paid thy debt worthily’) depending on the gravity of its sins. I think the whole scenario takes place in Purgatory, which the Middle Ages believed was frequently visited by angels in the role of consolers; here they apparently act as gatekeepers as well.

This unique painting is an extremely important one, offering considerable insight into the Medieval Church’s beliefs about the nature and function of Purgatory – a place of cleansing fire (as described by the second captive soul undergoing purgation), but also a place where the prayers of the living might be solicited (the first soul), and, ultimately, a place of hope (the third).

* Dr Madeleine Grey of the University of Wales at Newport has suggested that this confusingly gnomic utterance stems from a misreading of the Latin on the inscribed scroll, and suggests an alternative – Miseremini mei saltem vos amici mei – which translates as (Have pity on me, at least you my friends.) This entreaty, from Job 19 (verse 21 has the closest post-medieval English version) was, during the Middle Ages, echoed in the Office of the Dead. This seems far more satisfactory to me, not least because it leaves the theologically dubious possibility of appeals to the saints from those undergoing purgation out of things – and I am grateful to Dr Grey for her suggestion.

The closest relatives of this painting on the site are those of the Doom (the Weighing of Souls) and the Three Living & Three Dead – so links to the Introductions to those subjects are at the top and bottom of the page. An even closer relative, however, at Chaldon in Surrey, is now on this site. The Swanbourne Allegory might in fact be regarded as the sole remaining thematic descendant of the very early Purgatorial Ladder at Chaldon. Comparison of the two can be illuminating.

¹ These notes are from Records of Buckinghamshire, Vol.III (1879); the translations of the Latin inscriptions are the anonymous author’s, with an occasional contribution from me. The original account in Records of Buckinghamshire is probably still available, and I shall consult it if it is.

² ‘The fear of death…’. The words ‘conturbat me’ [confounds me] may once have completed the statement. The ‘Timor mortis’ theme is found fairly commonly in medieval literature.